The disaster of the nuclear plant in Chernobyl has permanently inscribed itself in the history of Ukraine and world, and the history of nuclear power. The twenty-fifth anniversary of those dramatic events provokes a reflection and questions about the further fate of the place that, due to a human error and technology, entered the sphere of existential fears and an apocalyptic vision of the world impacted by omnipresent radiation. The word Chernobyl evoked horror in 1986. Nowadays, it still sounds alarming. The stigmata of radioactive contamination has eternally been entrenched in the thousands of square kilometres of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, has erased the cultural heritage of those areas and condemned the millions to be called “the victims of Chernobyl”.

Closed zones were created around the power plant after the disaster and three hundred and thirty thousand people were displaced. A Ukrainian act on the legal status of radioactive areas contaminated as a result of the Chernobyl disaster defines “The exclusion zone and the zone of absolute (mandatory) resettlements” as an area excluded from civil economic activity and administrated by the Department of the State of the Ministry of Emergency Situations. The legal restrictions in place allow the operation of companies involved in neutralising radioactive wastes and liquidating the power plant closed in 2000 and building the New Safe Confinement hiding the remnants of the rector No. 4 where the explosion occurred (to be completed until 2015) and also to revitalise the ecosystem, implement water protection measures and run specialised forest economy.

The Polesky State Radioecological Reserve was established in 1988 at the Belorussian side at the area of 2161 square kilometers, unseen anywhere in the world. Over twenty-two thousand people were displaced from the area. The reserve, supervised by the Ministry of Emergency Situations, was established to prevent radionuclides being transferred beyond the contaminated zone and also for radiological monitoring, planned forestation and scientific fauna and flora research in specific environmental conditions.

the island of fleeting happiness

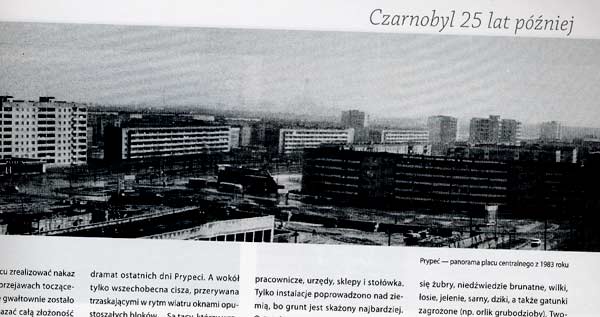

“Contemporary Pompeii”, ‘The City of Phantoms”, “The Ghost City “, “The City Museum”… How many names have been assumed for this place over the twenty-five years! Pripyat — a town of fifty thousand people erected in 1970 just four kilometres away from the Chernobyl power plant.

Built with imperial flamboyance for the power plant’s workers. A socialist piece of urban planning endowed with all the amenities one could wish for: community centre, hotel, hospital, numerous schools, kindergartens, swimming pools, gyms, shops, cafes, restaurants, stadium, broad streets, park and playgrounds… Only a temple was not there. The island of happiness in the sea of Soviet poverty and scarcity. The average age was not more than twenty-six years here, birth rate was one of the highest in the Soviet Union, most of the inhabitants had their own cars. Pripyat could relish its wealth for sixteen years only. All the residents were evacuated until 4.20 p.m. on 27 April 1986 because of reactors No. 4 explosion. They could take documents and money with them only. They left all their belongings in their apartments and service outlets. They thought they would soon come back. They have never come back.

in the world of emptiness

The world of urbanised emptiness, of desolate interiors, thrilling relicts, spreading nature remained. The place has a dual meaning for an architect or urban planner. On one hand it is return to large-panel prefabricated and industrialised buildings, to a unique heritage park of modernism which, desolated, has survived a quarter of the century without renovation and maintenance in an exceptionally good technical condition. It has survived despite common opinions on how worthless socialist construction is. It is so easy to recognise here the very familiar space of many Polish clusters of multi-dweller blocks of flats that emerged in our country after the war together with central economy. The following questions should be asked on the other hand: what will remain of our cities when we pass away? Who will take possession of the space we use? How this space inscribes itself into the relentless laws of nature and time? But also: what can we do to bring such places as Pripyat into life, to fill it with the buzz of everyday life? And if this should be done, at all? And yet, a monuments conservator or a museum professional asks a question: how to protect, describe and make available the space so painfully authentic and the everyday items scattered within such space, decaying from one year to another and looted? How to put into life the moral imperative in the real place to remember the signs of life that was going on here and was so violently stopped? How can we show the whole complexity of the issue of the displaced city, to see the fate of the evacuated, to become familiar with their existence and further history?

Journey to this place will also be meaningful for the lovers of literature, movies and computer games. The initial symptom of the looming catastrophe was first noticed in science fiction literature. The Roadside Picnic of the Strugatsky brothers of 1972 had anticipated the events that happened after the Chernobyl disaster, depicting to readers the mysterious “zone” full of anomalies and artefacts left by Aliens after their visit and also helplessness of those trying to face it. Andriej Tarkowski elaborated on this plot seven years later in his movie Statker and a Ukrainian company GSC Game World 2007-2009 released a computer game trilogy – S.TA.L.K.E.R.

The journey will be painful for a sensitive traveller. The remains of the city, the items of everyday use tread into the ground, child toys and garments covered with the rubble of decaying interiors, unsent postcards, personal documents — are all an open book easily illustrating the drama of Pripyat’s last days. And the omnipresent silence around only, interrupted with windows slamming in the rhythm of wind in empty blocks of flats… There are such who return here many times. Even illegally. The contemporary “stalkers”. They return to find answers to the questions bothering them. They return to feel free in the place intact with human activity for the last quarter of the century.

settle the zone

Travel to the Chernobyl zone for those horrified with the aftermaths of nuclear disasters and radiation will be surprising. Despite substantial soil and plants contamination, gamma radiation in the most of the Pripyat area does not exceed doses safe for life. A dosimeter taken for the travel indicating between 0.12 to 10.46 pSv/h confirms this, giving a yearly dose of between 1.05 to 91.63 mSv*), and there are places in the world with much higher natural radiation (e.g. a city of Ramsar in Iran — 285 mSv) where people live healthily for ages.

Almost four thousand people work in the “Exclusion Zone” and several dozens of companies operate, there are flats for workers, offices, shops and a canteen. Installations were fitted above the ground only as soil is most contaminated. There have been proposals emerging recently to make the zone more available to tourists. In December 2010, Oksana Nor, a head of Ukrainian State Agency “ChornobylInterinform” managing access to the zone announced that the hitherto restrictions will be eased. Euro 2012 is coming, it is hence expected that even a million people a year will want to see the “Ghost Town”. On the other hand, on the Belarusian side, President Lukashenko wants the displaced to return. The experts warn — we need to wait. Nature does not wait. Wisents, brown bears, wolves, mooses, deer, wild boars and also endangered species (e.g. Greater Spotted Eagle) appear on the areas free of human presence. A unique reserve comes into life. In the meantime, student works are being prepared at the Chair of Urban Planning of the Kiev National University of Construction and Architecture under the supervision of Prof. Maria M. Kushnirenko tackling the subject: “how to live in the Chernobyl zone?”. Is this, therefore, the time for architects and urban planners to voice their opinion after the years of research conducted by radiologists, psychologists, doctors and ecologists in the discussion over the future of the zone?

Author – Marek Rawecki (1958) – D.Sc. Arch. Eng., academic teacher at the Chair of Urban and Spatial Planning of the Faculty of Architecture of the Silesian University of Technology, Gliwice, Poland.

It is assumed that a deadly dose of gamma radiation for a human is about 3 Sv (editorial note).

Publication in journal “Architektura & Biznes“